Melissa Kwasny: BEWILDERING

“ The sole material for writers is language. Material choice for writers is then, I suppose, whether to write in prose or poetry or some combination thereof.”

Fall 2023 Artist-in-Residence at the American Prairie

Image of Melissa Kwasny

How was your experience as an Open AIR Artist-in-Residence?

Although I have been to other place-based residencies—the Taft-Nicholson Environmental Humanities Center at Red Rocks Wildlife Refuge, the Headlands Center for the Arts at the Marin Headlands—my experience at American Prairie was more than time set aside for writing. It was art camp and field school and research institute. It was like living in one’s own private nature preserve. It was magical and bewildering. Bewildering, because how does one understand and respond deeply to a place in two and a half weeks, eschewing “description’s false intimacy,” as the poet Forrest Gander writes, in the face of land soul-deep in millennia of indigenous habitation and millennia more of life for indigenous animals such as the coyote and bison? One day, we were driven to Medicine Rock, a Bewildering glacial erratic deposited on the flat prairie fifteen thousand years ago and then carved with petroglyphs of hoofprints, arrows, and spirals, a site of continuous visitation for people for thousands of years. How does one process that? Magical, as all encounters with nature seem magical to me: elk crossing the lovely Judith River at dusk, groves of ancient “cottonwood galleries” turning bright gold, coyotes curious and unafraid, and the reintroduction of over four-hundred buffalo, some direct descendants of the last few left on the prairie by 1882. The fact that they are back, after almost 150 years, and that I could see them, brought tears to my eyes.

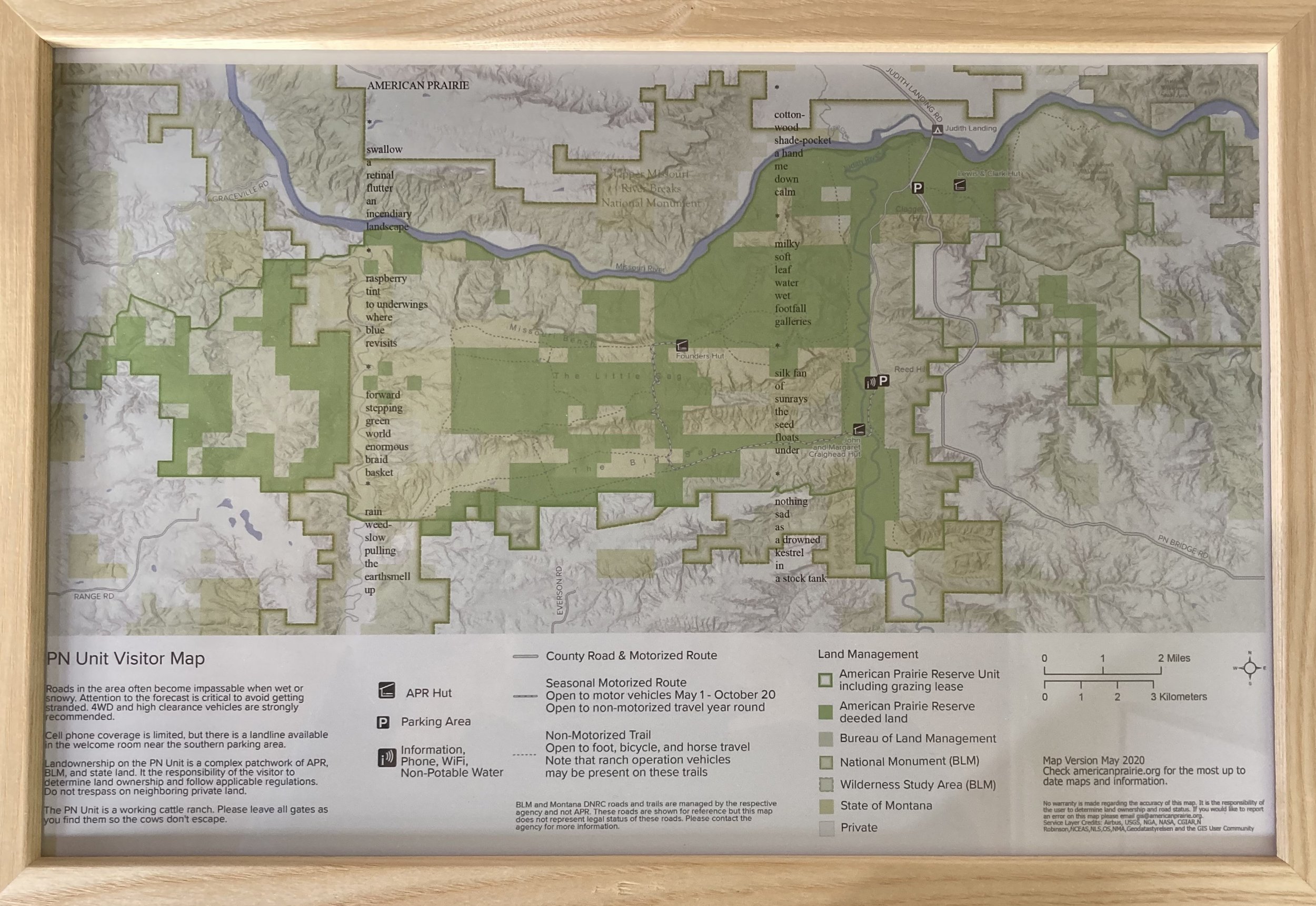

PN Property at American Prairie

What was your research process during this time?

Brandon Reintjes, curator and visual artist, Delia Touché, a Lakota printmaker and quilter, and I spent the first week of the residency on the Judith River, in a one room yurt, without internet, cell service, running water, and with limited solar generated electricity The second week, we shared a house on the prairie hours away on gumbo roads from any town. Poets are fortunate because our tools are lightweight and portable: a pen, a notebook, a bottle of water, the creative imagination. I spent most of my days outside, exploring, listening to the land, and writing. The staff at American Prairie were unbelievably generous with their time and expertise. How not to be grateful for biologists and botanists as guides? I saw my first burrowing owls squatting atop prairie dog mounds. We were shown ancient buffalo jumps and buffalo stones. We were driven at dusk to watch the bison herds moving, always moving. We learned about attempts to stop the black-foot ferret from extinction and about restoration of the original short grass prairie. Early mornings and evenings, Delia, Brandon, and I had many wide-ranging conversations about colonialization, conservation, reparation, refuge, restoration, rewilding.

Like most writers, I came with a lot of books, but I gave them up for the finely curated libraries at both sites: histories of the A'aninin and Nakoda at Fort Belknap, Yellow Wolf’s account of the flight of Chief Joseph’s band, which ended not far from here, Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History by historian Dan Flores, studies of prairie dogs and bison. I didn’t know that the coyote, unlike the wolf, is indigenous to the Americas. The dog descended from the wolf, which came here from Siberia and northern Europe, but the coyote originated here. Like many of the tribes have always claimed about themselves. It’s funny how white people want to believe that the continent was a blank slate, that anything and everything came across the Bering Strait from Europe. I remember hearing my Indian friends talking about the Strait: “The Bering Strait theory is right except they got the direction all wrong.” The dates of human presence keep moving back. Human remains are dated 12,000, then 14,000 years old, and now fossil footprints found in New Mexico a thousand years older. I read that Judith Landing, downstream, where the river empties into the Missouri, is an ancient burial grounds. Of course, it is. Isn’t everywhere? “It took little over than half a century to clear the Great Plains of that ancient population of animals, which during spans of good weather must have approached 25 to 30 million animals,” Flores writes.

Landscape at American Prairie

What are you up to now (post Open AIR)?

While I was in residence at American Prairie, I immersed myself in three projects. One was to choose seven words that came to mind when I thought of the deepest encounter I had during the day, words that captured the sensorium of a moment, much like a haiku attempts to do. I would then arrange and rearrange them vertically, one on a line, until they provoked a kind of stairstep resonance. This was a simple exercise in keeping my head out of the clouds. (I chose my favorites and reproduced them atop two maps of the different American Prairie sites where we stayed.) The second was a daily letter to Darby Minow Smith, an environmental nonfiction writer who was, at the same time, writing me from a residency in the Arctic Circle. That project has left me with dozens of pages of reflections on restoration and preservation, on American Prairie’s project of rewilding, and on new concepts of “place.” I am not sure what I will end up doing with them, though I know they will find their way into a future work. The third were notes toward poems—images, thoughts, quotations—that I am working on now.

“American Prairie PN” poem printed on map of American Prairie by Melissa Kwasny

How would you describe your work?

All seven of my books of poetry, along with a collection of essays Earth Recitals: Essays on Image and Vision, and a nonfiction book Putting on the Dog: The Animal Origins of What We Wear, have been concerned with the natural world and the historical and diverse ways different peoples conceptualize our relationship with it. How do we have a relationship with the natural world in our perilous times? What can we learn about being human from the non-human forms of life? What part does language play in this search and what part the various philosophies of both Western and indigenous cultures? During these years of pandemic, of increasing environmental degradation and global warming, rising fascism, and, personally, the loss of friends and my mother, I am also interested in what part the natural world plays in healing (including healing from grief) and restoration.

Have your material choices changed over the years?

The sole material for writers is language. Material choice for writers is then, I suppose, whether to write in prose or poetry or some combination thereof. In my career, I have written both, though I am primarily a poet. For poets, there is the choice between different forms of arrangement—lines, stanzas, meter, rhymes. When I first began publishing (long after I began writing, I want to note!) my poems were written in formal, tightly controlled stanzas dense with images. I loved the work of Louise Glück, H.D., and Lorine Niedecker, and the short Native songs translated by Frances Densmore. At some point, I felt the urge to include more of my thought processes into my poems, to incorporate my readings and conversations along with the images, and so, the lines became longer, the poems looser in structure. Eventually, I turned to the prose poem, influenced by poet René Char, in an effort toward more fluidity between image and statement. Lately, I have returned to writing (mostly)in lines as a way to break up the prose!

Bison on Sun Prairie property at American Prairie

Like to know more about Melissa? Click HERE!